Today I would like to talk about You, Me and our potential sales conversation.

I’m talking about you as the customer and us as the supplier.

First, this is a long email, so go and get a cup of tea or coffee as this could take some time to read.

Over the weekend, I was sitting with a few of my mates talking about the challenges of running a business. We’re a pretty diverse bunch – there was a project manager, a fitness instructor, a plumber, an aluminium fabricator and a financial adviser. (Sounds like the start of a joke. Trust me, there is no joke involved here.)

Even though we are all operate in different businesses we all agreed on one thing. There seems to be a massive disconnect between where the customer is when they first approach a supplier and where the supplier is upon that first introduction.

Let me explain how I see it, but please tell me if I’m wrong.

At the first point of contact the customer will have an idea in their head on what they want and what price they are willing to pay. Some research may have been done prior, but if it is a complex product it may be the phone call that is the first point of reference.

From the business owners perspective, he hears a simple request but straight away thinks of the different variations and solutions that may come into play in order to address what the customer requires.

There lies the disconnect!!!!!

The customer wants a product and a painless solution to a problem. Combine that with a great price, minimum fuss and no ongoing issues.

The supplier has several options in mind that may affect the working solution and price, all of which are dependent on the customer’s unique requirements.

So whilst the customer wants a simple solution, the suppliers head is racing with options.

And that, my friends, is where we are at on a daily basis…..

Example of a typical sales conversation within F.E.S. TANKS

If I relate this to what we hear daily within our business, hopefully it will help you understand our position and also help you think about the options YOU need to consider.

Customer: Hi, I was after a price for a ????? litre storage tank delivered to a location.

F.E.S. TANKS: Yes, no problem, that price is $$$$ + freight + GST.

Now that is breaking it down to its simplest form, the supply of just a stand alone tank. However this is rarely what customers are after…

What do customers really want?

Customer: I am after a price on a ????? litre storage tank.

What the client usually means is: I am after a storage tank with a pumping package as a finished self-contained unit. I want it delivered to my place of work as a plug and play solution so I can fill it up with fuel, turn it on and start using it. No fuss, no hassles. Job done and all within my budget of $$$$.

So we have to ask more questions…

F.E.S. TANKS: Okay, no problem. Bunded storage tank, simple. But we have a few more questions to understand what you will you be using it for and what are your exact requirements?

What is the salesman’s requirement here?

We need to know…

- Maximum capacity of storage you’re looking for?

- Product to be stored in your tank? Diesel, petrol, jet A1, waste oil…

- Do you require a fuel pump for filling purposes?

- Is power supply on-grid or off-grid? 12V, 24V or 240V delivery system…

- Do you need a fuel management solution or a simple metering system in place?

- Do you require specific pumps, bowsers, hoses and other fittings?

- Normal flow or high flow rates?

- Manual or automatic shut-off nozzles?

Hopefully you can see the two different thought processes going on here, with completely different considerations behind them. That said, the one common aspect of both parties is…….PRICE

Both parties have to get what they want for a mutually agreeable price. That means a price where the customer feels like they are getting value on goods and services. It’s also a price where the supplier feels they are delivering a fit for purpose product that is reflective of the customer needs but also reflective of their time, effort, experience, and one that is sustainable from a business perspective.

Both parties need to gain from this sales experience.

Business is fundamentally underpinned by relationships. Long term business relationships are underpinned by both parties continually gaining something along the way. These relationships break down over time because inevitably one party feels the other is gaining more at the expense of their misfortune.

So, long story short. Price doesn’t shift (in principle) so something has to. What changes is the mindset of both parties as they move towards that middle ground where both parties benefit.

Now you as a customer reading this will know where you mindset is relation to what you want. What I want to do is explain it a little more from our perspective, with the goal that you may be better informed and have a better understanding of the considerations when looking to buy a Bunded Storage Tank.

What you as a customer should consider when buying a fuel storage tank

-

Tank Storage

You will have an understanding of your operations and fuel usage. That will also give you an idea of the size of tank you require for storage. That part is simple.

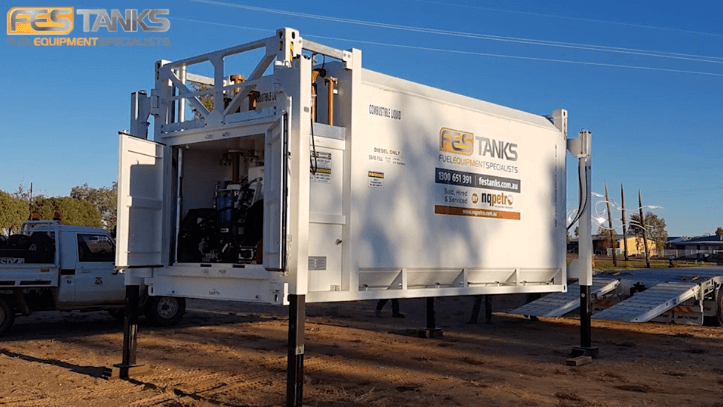

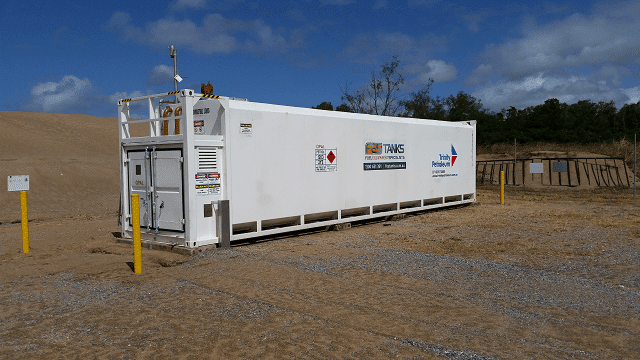

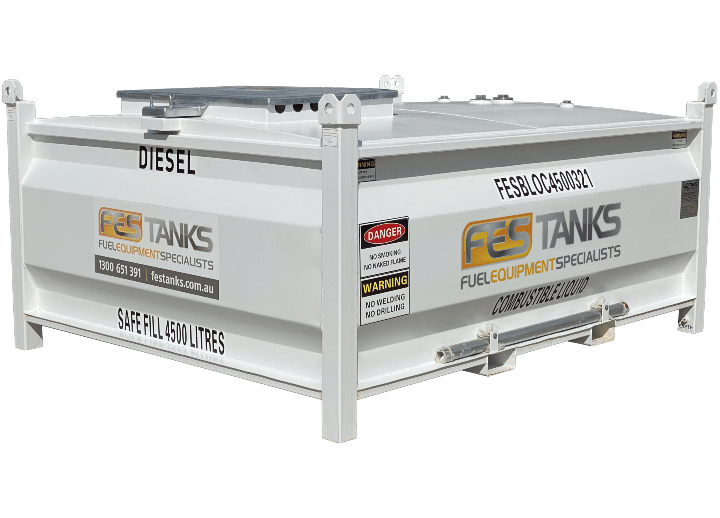

We have a range of bunded tanks ranging from 1,000l to 110,000l plus. They are easily adaptable to store different fuel types. They are environmentally friendly with their dual compartment systems (a tank within a tank) as well as being simple to move. They are a precision engineered product that is compliant with all Australian standards and finished with a paint finish that is guaranteed to deliver years of outdoor protection. Job done really.

-

Fuel Pumping

Yes, our tanks are great for storage, but what good is a fuel tank if you can’t get the fuel out of it?

This is where the complexity starts to build with multiple variations and options all very much dependent on YOUR unique situation.

So consider this please, in order of priority:

- Fuel type?

- Do you want to run off mains power or another power source (12v or 24v)?

- Do you want a pump only or do you want it metered for accountability?

- What sort of flow rate for delivery do you require? Standard or high flow?

The options on pumping gear are endless. Take a look at some of the pumping kit that we have in our online store to get an idea.

And there you have it. This is just a short list of things to consider, but it is better that you consider them prior to making that first call.

Of course if you are a big operator with big fuel volumes, you will have a whole list of other requirements and this is something that would need to be discussed one on one. For the small to medium operator let us continue.

Costs of Course!!!

Each one of these options listed above will have a cost implication, and this is a cost that needs to be factored into to your overall budget.

The best way to address this is by an example.

As a general rule of thumb I would allow 15-20% of your overall budget for pumping equipment. Of course that is very much dependent of your specific requirements so that range could go up or down depending on the simplicity or complexity of the brief.

YOUR BUDGET ($$$) = 80% TANK ($$$) + 20% PUMPING GEAR ($$$)

By using this formula you should you have a good level of expectation when looking to source a complete storage and pumping solution. However give us a call and so as we can discuss your situation and structure a package that is perfect for you.

Thanks for your time.

Daryl Cygler

(on behalf of the F.E.S. TANKS)